Interpreting kihon during everyday workouts. Everyone knows that the kihon is important, I think everyone has heard that an average workout should be at least 50% of the kihon, but many people neglect and prefer to practice only kata.

For interpretation, let us first unify what we mean by Kihon, Kata, Body Consciousness, and Muscle Memory which can be improved by repetition.

Kihon – (基本, きほん) is a Japanese term meaning „basics” or „fundamentals.” The term is used to refer to the basic techniques that are taught and practiced as the foundation of most Japanese martial arts.[1][2][3]

The practice and mastery of kihon is essential to all advanced training, and includes the practice of correct body form and breathing, while practicing basics such as stances, punches, kicks, blocks, and thrusts, but it also includes basic representative kata.

Kihon is not only practicing of techniques, it is also the budōka fostering the correct spirit and attitude at all times.[4]

Kihon techniques tend to be practiced often, in many cases during each practice session. They are considered fundamental to mastery and improvement of all movements of greater complexity.[5] Kihon in martial arts can be seen as analogous to basic skills in, for example, basketball. Professional NBA players continue to practice dribbling, passing, free throws, jump shots, etc. in an effort to maintain and perfect the more complex skills used during a basketball game.

From: wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kihon)

Kata – s a Japanese word (形) meaning literally „form” referring to a detailed choreographed pattern of martial arts movements made to be practised alone, and can also be reviewed within groups and in unison when training. It is practised in Japanese martial arts as a way to memorize and perfect the movements being executed. Korean martial arts with Japanese influence (hapkido, Tang Soo Do) use the derived term hyeong (hanja: 形) and also the term pumsae (hanja: 品勢 hangeul: 품새).

Kata are also used in many traditional Japanese arts such as theatre forms like kabuki and schools of tea ceremony (chadō), but are most commonly known in the martial arts. Kata are used by most Japanese and Okinawan martial arts, such as iaido, judo, kendo, kenpo, and karate.

From: wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kata)

Body consciousness – The concept and basis of spatial orientation: body consciousness, body scheme, body image, praxia and dyspraxia.

Most of our activities presuppose knowledge of the spatial world. An essential condition of human existence is that we interpret and use spatial experiences. Accurate coding of the position of objects in our environment is a critical aspect of human behavior. Understanding the potential of spatial situations is also important from a biological and psychological point of view (Huttenhocher and Lourenco, 2007). The basic condition for spatial orientation is the knowledge of the mechanisms of our body and our movements.

Without spatial coding of perceived phenomena, we cannot adapt to dangerous spatial situations, we cannot solve the reorganization of movement, thus avoiding obstacles and defending ourselves effectively. Children with learning disabilities show typical reactions at this time: they fall a lot, are caught in dangerous situations, walk on stairs with their feet side by side, and so on.

“Knowledge of space and orientation in it is an essential component of human intelligence, a separate segment of cognition within cognitive abilities” (Györkő, Lábadi and Beke, 2012,106).

The authors also suggest that the nervous system mechanism of spatial orientation is a well-defined system. The most significant brain areas are: “posterior parietal cortex, prefrontal and parahippocampal area, and hippocampus” (Györkő, Lábadi, & Beke, 2012, 107).

The success of the orientation and the development of the spatial approach are determined by the quantity and quality of the information.

Spatial view is the ability by which man perceives objects according to their spatial relation.

The observer must navigate between different environments, different objects, different spatial situations. Spatial perception is vertical to horizontal identification as well as mental rotation as well. Our spatial experience is determined by the boundaries of our own body and consciousness in the first approximation, but since there is no obstacle for our thinking and culture to gain and experience experiences beyond the boundaries of the body, this perception of space varies.

Above all, we continue to perceive and map out reality outside the body by turning around or looking at it, so that we can realistically experience that we are in the „center” of the visible world, the radius of which we can increase with our own spatial movement.

Spatial perception is the process of parallel perceptions: two aspects must be validated simultaneously: comparison to oneself (view-centered space) and comparison to spatial objects (object-centered space). At the same time, you need to detect the whole space at the same time and arrange the sub-information in it.

Such spatial information can be: position, distance, relationship to each other, magnitude.

The content of the communication also includes spatial information. Therefore, e.g. if a text also contains spatial information, we make spatial judgments for comprehension. Example: “That school. into which I had gone to the age of a great Dean, he was looking at the market with many windows. His gate also blackened out there, like some big, open mouth that always asks for food. ” (Ferenc Móra: Furfangos Cintula)

Spatial orientation is accelerated by the experience of permanent spatial positions. The fence is always in front of the house, the TV on a table, etc. Based on these preliminary expectations, the recognition of the spatial situation is accelerated, as a special stimulus a special and permanent connection is established between the situation of the object and its environment (Györkő, Lábadi and Beke, 2012).

In addition to preliminary expectations, spatial coding is also aided by the cognitive map (Tolman, 1948). A process consisting of a series of psychological processes that memorizes, encodes, stores, retrieves, and decodes information about the everyday spatial environment. The experience gained in space is recalled in a given situation.

The distances traveled every day seem shorter, we think of the rarely visited places as distant. We consider our own neighborhood to be friendly, other parts of the city to be foreign, or downright bad neighborhoods. What is distant and what is close, what is our own and what is foreign is, of course, always a subjective, a function of prior experience, motivations, abilities.

Perception and movement are inseparable. The experience of spatial orientation is gained mainly through movement. In this movement is an adaptation process, giving constant feedback. (Huba, 1995) The pattern of movement is therefore decisive among the information recorded during the route of a spatial situation or approach.

To solve a spatial task (we start somewhere) we need to know the spatial information, e.g. direction, distance.

Muscle memory – The ability to reproduce a particular movement without conscious thought, acquired as a result of frequent repetition of that movement.

From: https://www.lexico.com/definition/muscle_memory

When practicing iaido, jodo, or kendo, it is very important that the techniques are performed with the right quality, precision, and be recognizable. As an essence of this, I emphasize on practicing the kihon slowly, the knowledge of the exact beginning and the exact end of the movement, concatenation and adherence. What do I mean by that?

Kihon’s slow practice – the programming of the human body into a new movement can be mastered and developed with many repetitions, with slow movements, with attention. There are also aggravating factors, such as reprogramming of already learned bad habits, movements, differences in the speed or pace of movement between the movements that cannot be followed by the eye and the movements of the right-left, lower and upper bodies. As we practice these, the role of our attention and conscious practice is intensified, an integral part of which is the speed with which the movements are performed. Choosing a good speed is a prerequisite for practicing, you have to choose the right speed where attention can follow the motoric movements, and in a good case it can also influence the movement (familiar? At the end of a kata I think about what I did or then I remember what I wanted to practice, so the speed was too fast, my mind is lagging behind.)

Tip: You can help yourself by making a video of the kihons, where you can immediately check the execution of the movements while practicing, and you can later understand why the mistakes are made.

Knowing the exact beginning and the exact end of the movements – if you consider the kata as a whole, then the kata consists of kihon and connecting elements in terms of movement (speed, rhythm, sequence are not dimensions of the kata that I have not listed here). When practicing a kihon, it is easy to recognize the beginning and end of the kihon, during the kata this is not so clear in many cases. Consder the kata Ropponme, Morotezuki, as doing kihon exercises of turning and cutting (kirioroshi). Where does the kihon start, when do I have to do the kihon based movment in the kiri? During the exercise, if I consider the kihon as the base point, then the body consciousness will be the compass in the kata, where my movement meets the pre-practiced kihon execution point (illustrative buttercup video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cxyYjA2jTHY&ab_channel=JustinVillar)

Concatenation – In katas, I call the transition between kihon move(ment)s as “connecting elements”. These movements may seem completely different between kata and kihon, although they don’t really have to be different. To make it easier to imagine, I would like to illustrate with an example learned from Gábor Hábermajer sensei. The corner points described in the ZNKR iaido manual outline the shape of the kata, like the owl in the picture with the numbered dots. – »

In learning the form at the beginning we only try to follow the points, so when drawing we use straight lines in order. Then once we know the picture, we start playing with the lines, using arcs, thicker or thinner lines, colors, thus building up the whole picture at the end. These are my connecting elements, and the dots indicate the beginning and end of the movement, as we saw in the buttercup video.

Sequence – by the term sequence I mean the dimension of the movements, where the sequence of execution of the movements determines whether the movement makes sense or not. A simple example of this is Ju Nihon me Nukiuchi, beginning of the kata. The correct order is the hand on the sword, with the left foot stepping back, the hand raises the tsuka, and then the right foot stepping back, pulling the sword directly over the head, thus avoiding getting our hands in the way of the opponent’s cut. In the same way, also the order in Ukenagashi the left and right hands, metsuke, hips and feet use in a different rythm. The element I call sequencing, to which most practitioners respond first, is “woww,” “easy to say,” “I see, I understand, but I can’t do it”. In most cases, this dimension seems elusive in the use of body consciousness used in everyday life, we do not encounter this so emphatically, so it is unknown. This is an obstacle in our minds that needs to be overcome and understood that it is also just a technical element that needs to be practiced through conscious practice.

Conclusion

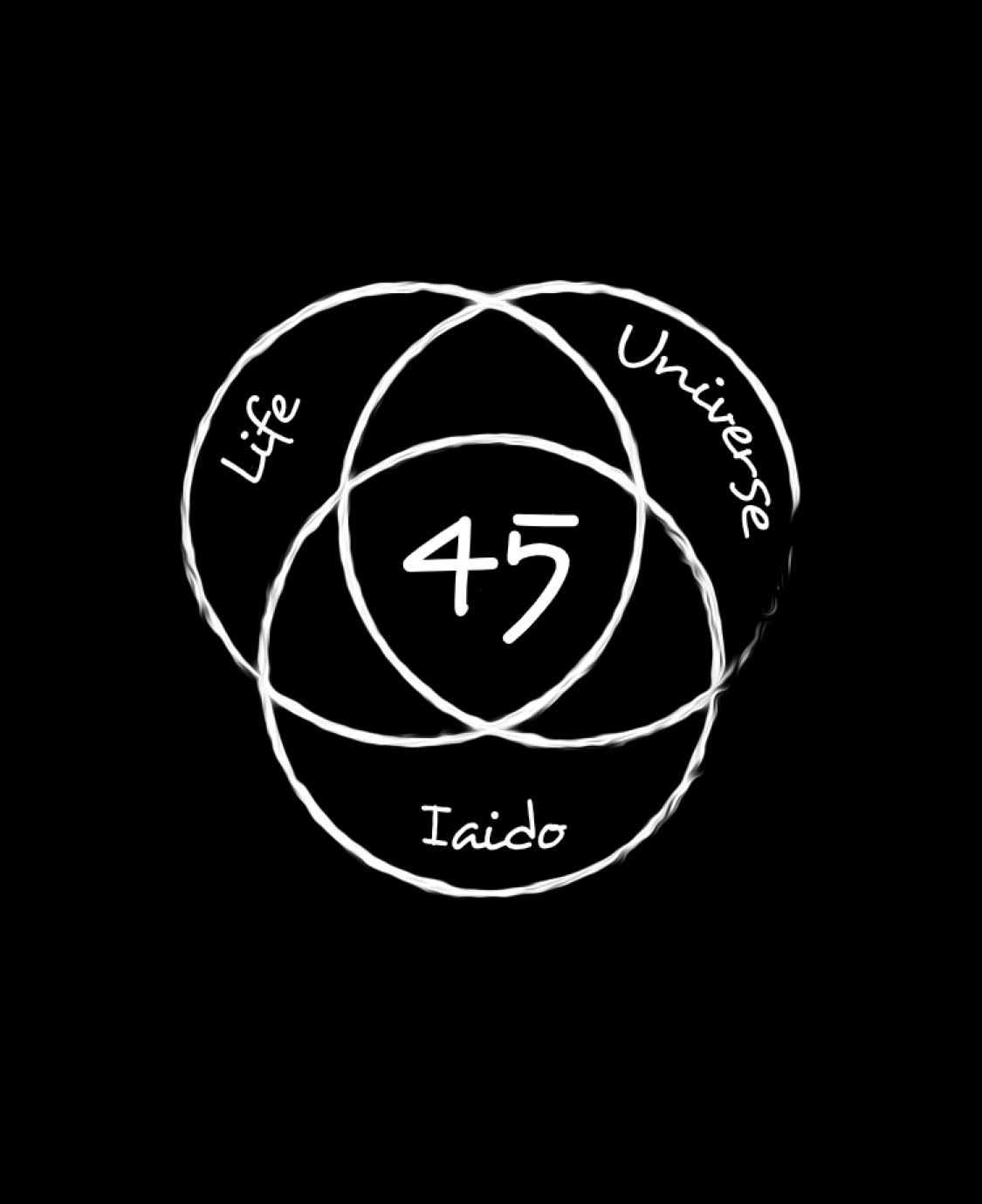

Once we have managed to come to a common denominator with the terms detailed above, it is only one step to understand the practice of kihon.

When performing the movement of the connecting points, I must recognize with body consciousness the starting point where the kihon begins, then perform the kihon, with the experience gained during the conscious practice of the kihon, and begin the next connecting element.

What can help us? It has happened to everyone that when correcting a move, the new movement is strange or uncomfortable. This feeling can be our best friend as it warns us if we are performing the movement differently than usual. So, if a new movement is uncomfortable, I need to pay attention to whether or not I feel that discomfort while practicing. If I don’t feel it, chances are I didn’t execute the movement in the new, right way what I wanted to practice. This feeling will, of course, go away sooner than it would have been built into body consciousness, i.e. muscle memory, so it cannot be fully built on that, but it can become a very good point of feedback during initial practice.

More ideas

– About the objection. Countless times I have experienced myself that I have noticed a mistake, but I did not let the existence of the mistake reach my consciousness, I was forgiving myself and I forgave myself for the mistake, because it is small, not important … blah, blah blah, blah blah blah blah ….

I’ve heard many times from practitioners that I can’t do this and I’ve been told logical, well-structured reasons from which I too could draw excuses for myself for not doing it.

Then I noticed that this was completely against my goals of wanting to understand and execute shapes better and better. That’s when I started allocating my resources differently. Instead of looking for excuses, for example, I started thinking about how I could do well. Instead of a lenient attitude towards myself, I started making a schedule: now I don’t have the capacity to deal with the bug I discovered because I’m working on another fix (it’s almost impossible for me to fix multiple things at once, I’m still wondering if that’s just an excuse: D), so take notes and I put it in a column so I know I still have to deal with it.

– Discipline cancellation. Everyone comes with their own life experience and this will be their sure point, so in case of uncertainty, you come back here, even if you don’t notice it. An example is the use of force when cutting: a common mistake for beginners is that the magic of the sword’s voice leads them to force rather than technique. This is when a more experienced practitioner sees it as hitting mammuts to death with a jerk instead of cutting with a sword. In the HiraBu dojo, we tend to hold a tamashigiri session every year, the main purpose of which is to understand the hasuji and break the “discipline of strength”. The task while cutting is to determine the minimum force with which the mat can be cut. As a result, everyone is usually surprised, you don’t need strength. Nevertheless, returning to the dojo remains a serious concern for the mammut strike. So the discipline of using force has not been overwritten. It is a good advice that the disciplines of facts and sensei are often more credible than our own feelings as we move into a new field where we often go blindfolded.